Embracing the Climate Double Dividend and Exploring the Transition Towards Plant-Based Diets

Paul Behrens

Leiden University

Zhongxiao Sun

China Agricultural University

“Without deep transformations of the food system, we will not stay within planetary boundaries”

Food production has huge environmental impacts, from biodiversity loss to soil degradation. Food systems also drive around a third of global greenhouse gas emissions. We need rapid and deep changes in food systems not only to address these environmental harms, but because even if we were to entirely decarbonize the energy system, the food-system alone can push the planet beyond 1.5°C warming or even 2°C warming by the end of this century.

Researchers have identified three main pillars to this food transformation: a shift to plant-based diets, reductions in food waste, and improvements in food production. However, these pillars are not created equal - multiple studies show that the largest decarbonization potential lies in shifting to plant-based diets, especially in high-income nations. Livestock products generally result in much larger emissions than plant-based options, especially red meat via the gases from manure and livestock belching which releases methane. Yet, while we know that plant-based diets have a huge potential for decreasing greenhouse gas emissions, there is an important simultaneous opportunity.

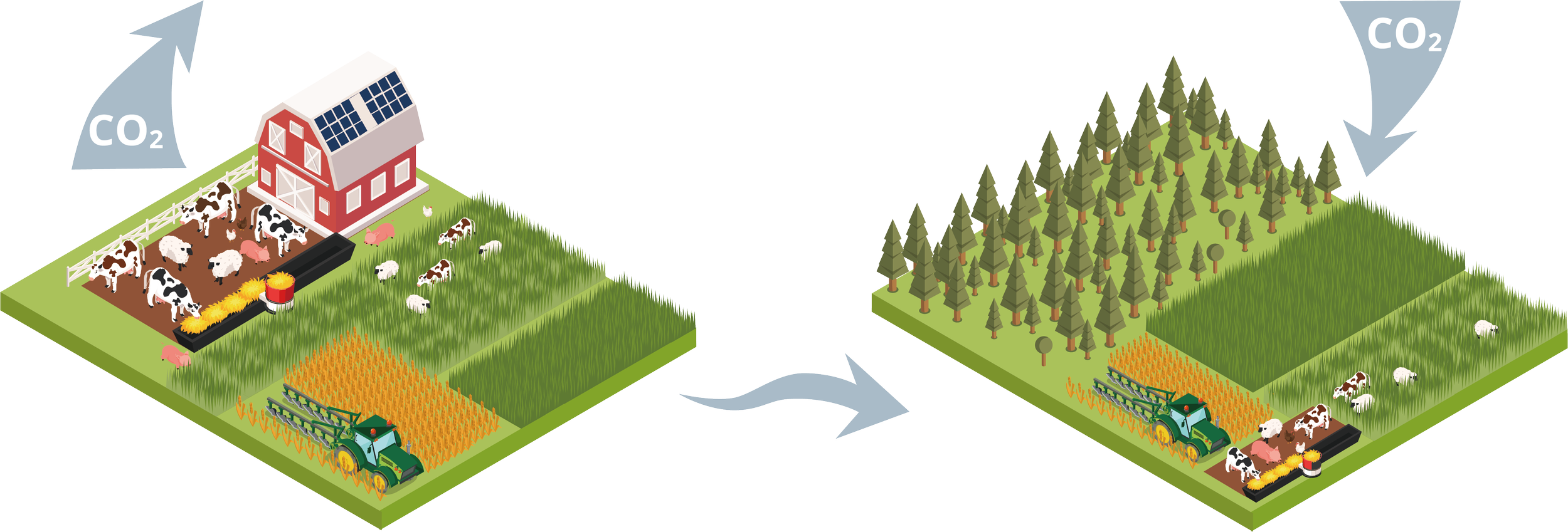

Agriculture currently occupies around half of all habitable land on this planet. In fact, once we account for grazing and feed, livestock farming uses about 77% of agricultural land globally, yet it produces less than 20% of the world's supply of calories. The demand for feed crops and grazing land is the primary driver behind deforestation, especially in biodiverse regions like the Amazon rainforest. By shifting to plant-based diets we can not only reduce emissions from the food system, but we can reduce the land needed for food production, freeing up space for nature and biodiversity. As we save land for nature it will also drawdown carbon from the atmosphere into the richer vegetation, soils, and natural wildlife, resulting in carbon sequestration. This is what we call a climate “Double Dividend”.

In our Frontiers Planet Prize article, with several other colleagues from around the world we explored how shifting from average diets to plant-based diets would reduce emissions and free land for restoration. We explored how if people in high-income nations ate a healthy, plant-based diet—a diet designed by leading epidemiologists and doctors from around the world—we would reduce emissions from the food system by around 60% while saving an area of land approximately the size of the EU. If we were able to save this land and return it to nature, we would be able to draw down around 14 years of global agricultural emissions into the vegetation and soils. We chose to look at high-income nations only as these countries typically have more plant-based options available in their supermarkets and restaurants.

We are now exploring the many other environmental opportunities from a food system transformation—especially the shift to plant-based diets. For example, we are working on how these diets could increase resilience to food shocks, reduce air pollution, and improve biodiversity. This touches on many of the planetary boundaries. In fact, food is either the main driver or the second largest driver of all but one of the planetary boundaries. Without transforming the food system, there is no safe operating space for society.

Yet, while many of the potential benefits are clear, implementing and scaling up these dietary changes pose significant challenges. Cultural, economic, and infrastructural barriers must be addressed to facilitate widespread adoption of plant-based diets. Additionally, effective land restoration practices and policies are essential to maximize carbon sequestration potential. We are working on how to help food producers, exploring how we might shift food subsidies in Europe and further afield, while considering their input costs, capital costs, and other economic pressures.

A broader trend currently occurring in this field is the integration of different socio-economic factors with environmental outcomes to fully explore food system transitions from the supply-side (farmers and food production, like novel foods) to the demand-side (customers and their diets), and along the supply chain (processing, refrigeration, retailers, and more). Mapping and implementing food system transformations will require a careful coordination of production changes, consumption changes, research and development investment, land-use policies, public health measures, and more. This is an incredibly complex systems transition, yet a very exciting one as it represents a world that is more sustainable, resilient to climate change, and healthier for people over the long run.